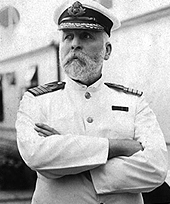

Edward John Smith

Date of birth: 27 January 1850

Place of birth: Hanley, Staffordshire, England

Marital status: Married

Spouse: Sarah Eleanor Pennington

Children: Helen Melville Smith (1898–1973)

Address: Woodhead, Winn Road, Portswood, Southampton, Hampshire, England

Crew position: Titanic's Captain

Date of death: 15 April, 1912

Cause of death: Unconfirmed; body never recovered