Side Menu:

Captain E.J. Smith - Aboard Titanic

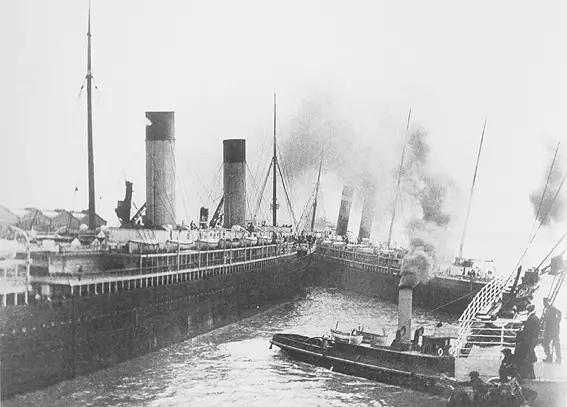

R.M.S. Titanic departing Southampton docks at noon April 10th, 1912.

(Click image to enlarge)

Smith relieved Titanic's first captain

- Herbert Haddock - in Belfast.

The night before Captain Smith left New York for Europe to take command of the Titanic, he apparantly dined with Mr. and Mrs. W. P. Willie of Flushing, Long Island:

At that dinner Captain Smith, according to Mr. Willie, was enthusiastic over the prospects of his new command. He said he shared with the designers of the vessel the utmost confidence in her seagoing abilities, and told Mr. and Mrs. Willie that it was impossible for her to sink. He looked forward then to the most successful days of his seagoing career, and especially dwelt upon the idea that the Titanic's appearance on the Atlantic marked a high point of safety and comfort in the evolution of ocean travel.

He regarded that vessel as one that would stay above water in the face of the most unexpected trials. Even if a part of the hull should be seriously damaged, he said, there need be no doubt that she would reach port. "From what I know of Captain Smith," Willie said, "he would be the last man to leave the ship if it was sinking." (Washington Post, April 18, 1912 courtesy of George Behe)

Leaving the Olympic in Southampton smith joined Titanic on the 1st of April, in Belfast for her sea trials, which were cut short due to poor weather. He had relieved Titanic's first master Captain Herbert Haddock of his duties - Haddock returned to Southampton to take command of the Olympic, essentially swapping places with Smith. (For an indepth biography of Haddock check here).

Changing Officers

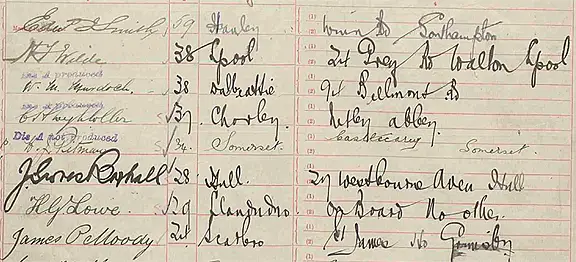

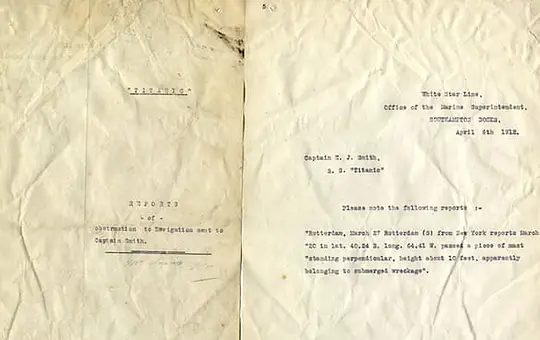

On 4 April 1912 the Titanic arrived at Southampton and docked at berth 44. According to the paperwork, E.J Smith signs on aged "59," although he was actually aged 62 at the time. Oddly enough, he correctly gave his age as 61 when in command of Olympic in 1911. A few days before sailing day, there was also a surprising announcement. Captain Smith, working on orders from the White Star Line, reshuffled the senior crew's positions to accommodate Henry Tingle Wilde as Chief Officer (as he had been aboard Olympic). This meant that Murdoch was bumped down to the position of First Officer, and Charles Herbert Lightoller to Second Officer, while David Blair was left out entirely, the other officers remaining the same. The decision was not necessarily Smith's, as Lightoller later recalls:

Owing to the Olympic being laid up, the ruling lights of the White Star Line thought it would be a good plan to send the Chief Officer of the Olympic, just for the one voyage, as Chief Officer of the Titanic, to help, with his experience of her sister ship. (47.)

Titanic's Crew Agreement document, with the signatures of Captain Smith and his officers, courtesy of National Archives, UK.

Evidence suggests that the demotion was primarily due to the White Star Line making use of Wilde who was waiting for his own promotion to captain of a White Star vessel. In Lightoller's article from the Christian Science Sentinel (December 1912) this is referenced when he writes:

"Shortly before we sailed from Southampton, Wilde, who was formerly chief of the Olympic, and who was to have been given command of another of the White Star steamers, which, owing to the coal strike and other reasons was laid up, was sent for the time being to the Titanic as chief, Murdoch ranking back to first, myself to second, and Blair standing out for the voyage." Christian Science Sentinel (December 1912)

Titanic's Crew Agreement document, including the

signatures of Captain Smith and his officers, courtesy of

National Archives, UK. (Click image to enlarge)

Additionally a letter from David Blair, originally assigned as Titanic's Second officer, dated 4th of April 1912 mentions "I shall have to step out to make room for [the] Chief officer of the Olympic who was going in command but so many ships laid up he will have to wait..." (On a Sea of Glass, p.58 54.). However the letter makes it unclear whether Blair was referring to Wilde being captain of the Olympic or whether it was another ship, which is more likely. A Mr Smith, a manager of a New York club for mercantile mariners, wrote in April 1912 saying that Wilde "would have been Captain of the Cymric two trips ago, only the coal strike and the tying up of some of the ships altered the company's plans." ("Portbrush letter" by Senan Molony 8.))

Either way, the new Chief Officer, Henry Tingle Wilde, arrived aboard ship sometime on the 9th of April, after coaling, crew recruitment, cargo loading and loading of food supplies had already taken place.

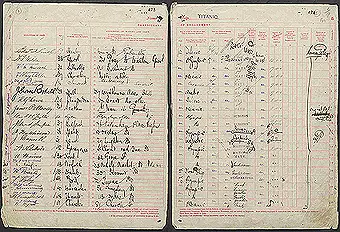

Obstruction report

On the 6th of April 1912, Captain Smith receives a personal report from Benjamin Steele, who was the marine superintendent for White Star Line at Southampton Docks, warning him of a potential obstruction ahead - the mast of a submerged wreck in the Atlantic.

A report to Captain Smith on April 6th, 1912, from the White Star Line marine superintendent about a potential obstruction on the maiden voyage.

(Click to enlarge)

According to The Guardian newspaper of April 15, 2016, when the document went up for auction that year, Auctioneer Andrew Aldridge said:

“This report was from the offices of the White Star Line’s marine superintendent at Southampton directly to Captain Smith warning him of a potential obstruction ahead. The obstruction wasn’t an iceberg but the mast of a wreck that had been reported by the Rotterdam, a Dutch liner that had travelled from New York. The obstacle would have done some serious damage and ripped a hole in the hull of Titanic had it gone straight over it.

“This was not a mass-produced document but a one-off report specifically for Captain EJ Smith. One of the major attractions to it is that it would have been in the hands of Captain Smith on the bridge of the Titanic. He would have read it and then given it back to whoever brought it. It later helped show that White Star Line acted responsibly up until Titanic sailed.”(The Guardian newspaper of April 15, 2016, source)

The irony of this report was perhaps not lost on Second Officer Lightoller, who later wrote in his book, Titanic and Other Ships (1935):

"Apart from icebergs, another inducement for the sailor to keep his eyes skinned is derelicts, that have been known to drift about the world for years, covering thousands of miles. Individually, they are a worse danger than icebergs." (47.)

An approximate plotting of the location of the submerged wreck. According

to Google Maps, the reported obstruction was indeed on Titanic's course.

Sailing Day: Cabin and Uniform

At 7am, on the 10th of April 1912, sailing day, Smith left Woodhead his home in Winn St, Southampton, wearing an overcoat and bowler hat and came aboard Titanic at 7.30 am and received the day's sailing report from Chief Officer Wilde to prepare for the Board of Trade muster at 8:00 am.

Once aboard Titanic, Captain Smith would have proceeded to his cabin and changed into his uniform.

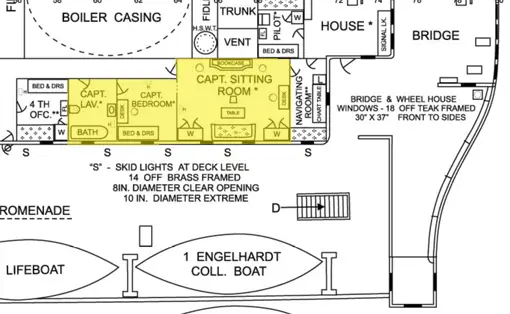

Captain Smith's quarters aboard Titanic highlighted in yellow.

His private cabin was situated on the forward starboard side of the Officer's Quarters and consisted of three rooms - a sitting room, a bedroom and a bathroom. The largest of the three rooms was the sitting room and could be accessed directly through the Navigating Room (Chart Room) which in turn was connected to the wheelhouse, which meant that Smith could be on the bridge within seconds if need be. The Sitting Room had a table, settee, wardrobes and a desk and could be possibly be used for entertaining guests or private meetings. The bedroom was connected to the Sitting Room and was very simple, consisting of a bed and desk. The Captain's Lavatory was fitted with a porcelain bath tub with intricate plumbing for both freshwater and seawater. Famously this bath can still be seen in the wreck.

A computer generated image giving an artist's impression of what the interior of Captain Smith's sitting room could have looked like - courtesy of "@rmstitanicdesign"

(Click to enlarge)

An alternate view of a computer generated image giving an artist's impression of what the interior of Captain Smith's sitting room could have looked like - courtesy of "@rmstitanicdesign" (Click to enlarge)

An alternate view of a computer generated image giving an artist's impression of what the interior of Captain Smith's sitting room could have looked like - courtesy of "@rmstitanicdesign" (Click to enlarge)

There are claims these two pieces of furniture - a sideboard and table built by Harland & Wolff - were destined for installation in Captain Smith's quarters.

For more information check this article here.

Smith's usual uniform was, as with the other officers, the "service dress" or "undress uniform, the most basic White Star Line uniform the officers would wear when on duty.

Notable features were the waist long jacket (Reefer jacket) which was double breasted and eight-buttoned (sometimes referred to as a "monkey jacket") with 8 raised White Star Line brass buttons, four to each side of the jacket, all bearing the White Star emblem. The material was 'navy blue' a deep, dark blue that is almost black in colour and most often of the "Melton" variety or "naval doeskin," a smoother, finely-woven wool. Under the jacket he would wear a white dress shirt, with separate collars and cuffs, with collar, turned down and a black silk tie. The Captain's rank insignia (4 stripes) was on both sleeves using black lace with an executive curl. And finally a cap worn with or without white "topper" depending on season (a white version of the uniform was used during the summer months).

Captain Smith's bath in his Titanic quarters, as seen now in the wreck.

For more information on the bathtub and its present condition

please check this article here.

However on special or more formal occasions Smith's uniform would change - instead of the waist long Reefer/monkey jacket, this would be changed to the knee-long jacket (Frock jacket), with a stand and fall collar, double-breasted, ten brass buttons featuring the White Star emblem. Also a noticeable part of this "Mess Dress of "Full Company Dress" uniform were the ceremonial gloves, mostly white, to be held in the left hand whenever photographed.

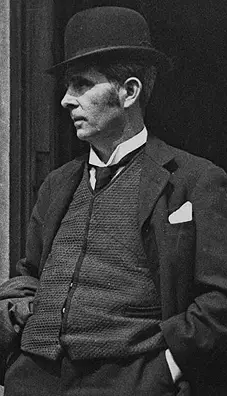

Captain Edward John Smith standing outside the portside Officer Quarters on the boat deck of Titanic while she was at Southampton during the morning of 10th April, 1912

(Click to enlarge)

So on the day of Titanic's maiden voyage Smith put on his knee long frock jacket and held his black (not white) cloth gloves in his hands and is subsequently photographed in two locations by press photographers who arrived on board at 10.30am. Firstly, he is photographed standing outside the portside Officer Quarters on the boat deck. Black gloves in hand, the First and Second officers' cabin windows are behind him. The rush to prepare Titanic for her maiden voyage is visible in the debris (with leaves and plant trimmings being brought onboard the night before) on the deck at his feet. He is photographed by three different agencies from three slightly different angles - the Newspaper Illustrations Ltd, Illustrations Bureau and Central News.

Above and right: Captain Smith in one of three different photographs taken of him on Titanic's port boat deck. (Click images to enlarge)

The second and more impressive location is the bridge, Smith seen standing somewhat pensively on the portside of the wooden navigational bridge, allowing us one of the only tantalizing glimpses into Titanic's bridge, with a large telegraph visible through the window behind his shoulder. The photograph is taken by the Newspaper Illustrations Ltd agency.

Captain Edward John Smith poses on Titanic's portside of the bridge on the morning of April 10th, in the only known photograph of Smith on Titanic's bridge.

(Click to enlarge)

But there was other pressing work to be done other than posing for the press. The crew muster, in which First officer William Murdoch called out the names of the crew finished at around 9am and at 9.30am the first class passengers began arriving. A boat drill was also performed for the Board of Trade inspector. At 11am the harbour pilot Bowyer arrived and readies the crew for the departure.

Once the he senior officers Wilde, Murdoch and Lightoller had submitted their reports to the Smith, then First Officer Murdoch reported the vessel ready to sail, and at midday Titanic began her journey, with more than 2,200 people aboard.

Early Mishaps

As the Titanic steamed along the River Test, the water displacement caused all six mooring ropes on the S.S. New York to snap ('reports like a revolver firing'.) and her stern to swing toward Titanic. Captain Smith or Pilot Bowyer promptly ordered the Titanic's engines stopped and then full astern, and tugs hurried to guide the New York to a berth a little beyond the Oceanic, on Dock Head. This quick action averted a collision, but by only four feet.

First class passenger Father Francis Browne captures on camera from onboard Titanic the moment the American Line's S.S. New York lines snap, almost causing a collision.

Another curious event happened once Titanic reached its first port of call - Cherbourg. The near collision had delayed departure for about an hour while the drifting New York was brought under control, and the Titanic arrived four hours later at 6.35pm in the French port of Cherbourg. Due to the size of Titanic and the lack of suitable docking facilities at Cherbourg the White Star Line operating two tenders -the SS Traffic and the SS Nomadic. Within 90 minutes 274 passengers boarded Titanic and 24 departed aboard the tenders.

It was on the tender Traffic, that a 'curious incident' involving Murdoch allegedly took place. According to a young French man by the name of Jules Munsch (1893-1915) who wrote a May 1912 account in Les Cahiers de l’Ecole Nationale de Rouen and only recently released in April 2012, First Officer Murdoch prohibited a French Naval officer Commander Leloup who was aboard the Traffic from temporarily boarding Titanic, an order that was subsequently overridden by Captain Smith and lead to Munsch and Leloup having a personal tour of Titanic. A translation of his account is as follows:

French Naval officer Commander

Leloup who First officer Murdoch

allegedly prohibited from boarding

the Titanic at Cherbourg,

which was overriden by Smith

"Then began the transhipment of passengers and baggage. The Nomadic, docked in port, carrying the first and second classes passengers. Aboard the Traffic, a curious little incident occurred. Commander Leloup, French Navy military, wanted to take the Nomadic to paid a visit on the Titanic. Having missed the departure, he embarked aboard the Traffic and wanted to cross the gangplank. Murdock refused, and Leloupe asked: "Is the Captain of the Traffic on board?" We sent for Gaillard who introduced himself: "At your orders, sir!" Leloup: " I want to know why a French naval officer is denied boarding of a foreign merchant ship in the harbor of Cherbourg?" Indeed, Lieutenant Murdock disobeyed a major maritime regulation by prohibiting a French officer access to the ship. Captain Smith was called and came himself to fetch Commander Leloup at the gangplank. We followed them eagerly, and took advantage of the honors of the gateway." (account courtesy of Tiphaine Hirou for the full account please see here)

Smith's Private Steward and the Final Photograph

Finally at 8:10 p.m Titanic departed Cherbourg bound for Queenstown. On Smith's orders Titanic made a series of long S turns, likely to test her performance and ready her for the open sea. Titanic arrived at 11.30 am on Thursday 11 April at Cork Harbour on the south coast of Ireland. Once again the docking facilities were not sufficient for a ship the size of Titanic and tenders were used to bring 113 third class and seven second class passengers came aboard, while seven passengers departed.

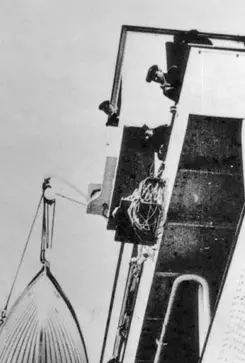

Captain Smith looks down from Titanic's

starboard wing cab as the tender Ireland

comes along side at Queenstown.

(Click to enlarge)

Smith is famously photographed as he watches the tender Ireland come alongside Titanic. Gazing down from the starboard wing cab, this photograph has often incorrectly been identified as the last photograph of Smith, taken by Father Francis Browne. However neither is true. This photograph was taken by Dr William McLean, a Sanitary Surveyor of the Board of Trade at Queenstown who took the photograph from the Ireland tender.

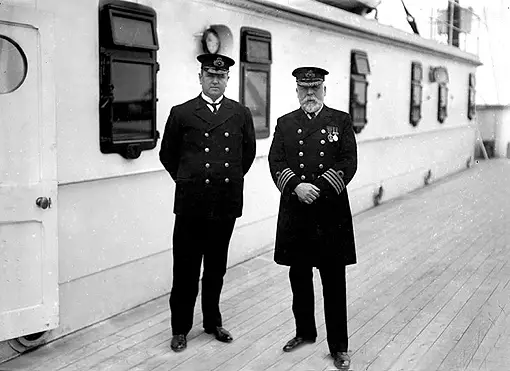

The last known photographs to be taken of Captain Smith is of him standing on the starboard side of the Officer's Quarters alongside Chief Purser McElroy. Taken by photographer Thomas Barker, the window to the left of McElroy is Fouth Officer Boxhall's cabin, while the next four windows belong to the Captain's rooms. There are two photographs - one wide angle and the other slightly closer.

Captain Smith with Purser McElroy outside the door way to the Officer Quarters while Titanic lay at anchor off Roches Point, Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland on the 11th April, 1912. This is one of two last known photographs of Smith.

(Click to enlarge)

The second photograph, slightly closer, of Captain Smith with Purser McElroy on Titanic's starboard boat deck while at anchor off Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland on the 11th April, 1912. This is one of two last known photographs of Smith, and is said to have been taken by Francis Browne. (Click to enlarge)

Captain Smith's private steward,

Arthur Paintin (Click to enlarge)

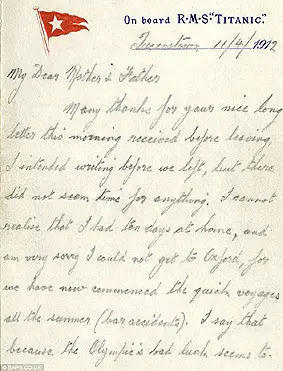

Smith also had his own private steward, also known as his 'personal valet', or "Tiger", 29 year old James Arthur Tiger Paintin, to bring his meals or messages. Paintin had worked under Smith on the Olympic and so was very familiar with the Captain. While Titanic was moored near Queenstown, Paintin wrote an intriguing letter to his parents in Oxford:

Captain Smith's private steward Arthur Paitin,

describes "bad luck" in his letter home.

(Click image to enlarge)

'Bai jove [sic] what a fine ship this is, much better than the Olympic as far as passengers are concerned. 'But my little room is nothing near so nice, no daylight, electric light on all day, but I suppose it’s no use grumbling. 'I cannot realise that I had ten days at home, and am very sorry I could not get to Oxford for we have now commenced the quick voyages all the summer (bar accidents). 'I say that because the Olympic’s bad luck seems to have followed us for as we came out of Southampton dock this morning we passed quite close to the New York which was tied up in the Adriatic’s old berth, and whether it was suction or what it was I don’t know, but the New York’s ropes snapped like a piece of cotton and she drifted against us. 'There was great excitement for some little time, but I don’t think there was any damage done bar one or two people knocked over by the ropes.'

It is worth noting Paintin's use of the phrase "bad luck" in relation to "accidents" that Smith had experienced with both Olympic and Titanic. But little could prepare him for how bad it would be.