Side Menu:

Second Officer David Blair

- Oceanic Disaster

After his heroic actions as First Officer aboard the Majestic, Blair had to step back to Second Officer when he was moved on to the Oceanic on the 28th of July 1913, until the 1st of January 1914. His White Star records once again mention holiday leave from 1/1/14 - 19/1/14. After a Navy drill (19/1/14 - 2/2/14) he returned to the Oceanic as Second Officer from the 2nd of February until the 11th of July. He was also joined by Lightoller, who from the 1st of June 1914 served as First officer.

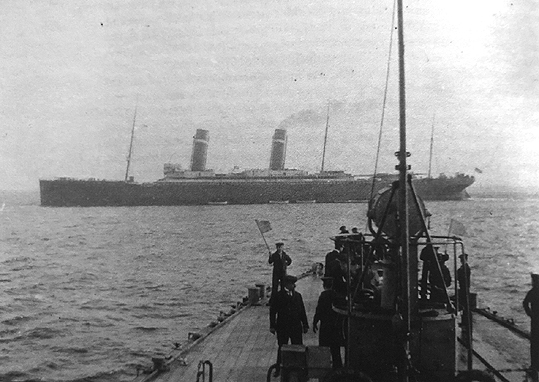

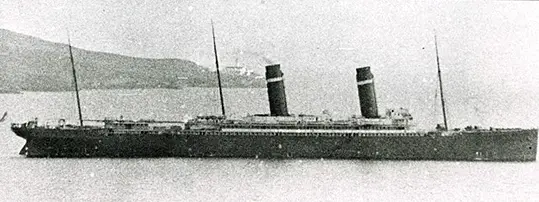

RMS Oceanic, aboard which Blair served as second officer.

(Click image to enlarge)

Initially the Oceanic continued on the New York route. But Blair's White Star Line records then note that he was in the "Navy" from the 1/7/14 - 24/6/19. In fact he was still aboard the Oceanic, but in a naval capacity.

The reason for this change is that on the 8th August 1914 the Oceanic was commissioned into Naval service as an armed merchant cruiser. The Oceanic had originally been built so that 4.7 inch guns she was to be given could be quickly mounted:

Oceanic was to patrol the waters from the North Scottish mainland to the Faroes, in particular the area around Shetland. She was empowered to stop shipping at her Captain’s discretion, and to check cargoes and personnel for any potential German connections. For these duties, she carried Royal Marines and Captain William Slayter RN was appointed in command. Her former Merchant Master, Captain Henry Smith, with two years' service, remained in the ship with the rank of Commander RNR. Many of the original crew also continued to serve on Oceanic. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Oceanic_(1899)

Disaster

On 25th August 1914, the newly designated HMS Oceanic left Southampton to take up her patrol role in the waters between the north of Scotland and the Faroes, travelling continuously in a standard zigzag course as a precaution against being targeted by U-boats. This made Blair's job particularly difficult:

Blair just now was a man under pressure: his was the responsibility for navigating this huge liner through these tricky waters, a job made all the more complicated by the continuous zig-zag course being steered to evade submarine attack. Blair was a very accomplished navigator in normal circumstances, but now his skills were being stretched to the limit. Even Blair would be hard put to thread the Oceanic through the eye of a needle which at times was almost what he was being asked to do as he pored day and night over unfamiliar complex charts, his eyes bleary with the strain. Blair had the most unenviable job of trying to plot courses first this way and then that, as each Captain took it into his head to order a change of course when the mood took him. In fact the whole business seemed like a ready-made recipe for disaster. (Titanic Voyager: The Oddysey of C.H. Lightoller, Patrick Stenson)

The Oceanic met with some initial success. According to Stenson:

"The day after leaving Lerwick a Norwegian barque was sighted and ordered to heave to. A search by the marines uncovered a single terrified German subject of undefined intentions who was brought back aboard in heady triumph. With their prisoner safely locked up in the brig, the Oceanic continued her patrol heading back north, but this time towards the tiny island of Foula, about twenty miles west of Shetland. Heading towards the island was dangerous, as it was known to have a "cluster of rocks and reefs which lay around her coast, in particular the dreaded Shaalds - otherwise known as the Hoevdi Grund -two miles to the east of the island". It was Navy Captain Slayter's idea to set course for the island, despite Captain Smith's warnings. (Titanic Voyager: The Oddysey of C.H. Lightoller, Patrick Stenson)

On the night of 7th of September 1914, Blair made a fix of their position, which was to lead to tragedy. There are various accounts of this, some which blame Blair directly:

Wikipedia: An inaccurate fix of their position was made on the night of 7 September by navigator Lieutenant David Blair RNR (previously assigned to, then reassigned from, the Titanic). While everyone on the bridge thought they were well to the southwest of the Isle of Foula, they were in fact an estimated thirteen to fourteen miles off course and on the wrong side of the island. This put them directly on course for a reef, the notorious Shaalds of Foula, which poses a major threat to shipping, coming within a few feet of the surface, and in calm weather giving no warning sign whatsoever. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Oceanic_(1899)

Scottish Shipwrecks: After stopping briefly at Scapa Flow the Oceanic headed out on her first patrol. As was usual in the area the captain set a zigzag course to attempt to hamper any attacks by enemy submarines. In fact, it was the difficulty of steering such a complicated course in waters often swept by strong tidal streams that was to be the undoing of the Oceanic rather than any enemy action. A fix of their position was made on the night of the 7th September by Lieutenant David Blair but, as the ship headed on the course intended by Captain Slayter towards the island of Foula, she was heading straight towards the dreaded Shaalds of Foula, a notorious reef east of the island which nearly breaks surface. (Source: https://www.scottishshipwrecks.com/oceanic-2/)

Titanic Voyager: During his [Lightoller's] watch the previous evening Foula had come into view and he had been with Blair in the chartroom observing him plot the ship's position, accurately taking his bearings from the north and south ends

of the island. During the night, while Lightoller was away from the bridge the ship had continued to zig-zag around the area, with Blair plotting the reckonings and laying off the courses as each alteration was ordered by Slayter. One arrangement which the two captains had managed to agree on was that Smith would take charge of the ship during the day while Slayter took over at night. At one point during the night, thick fog was encountered and the engines were stopped, but as dawn broke and Lightoller arrived back on the bridge to take his morning watch visibility, apart from a thin mist, had cleared and the ship was steaming in a calm sea at a cautious 8 1/2 knots.

According to Blair's calculations, the Oceanic was shown on the chart just now to be well south of the island and, working off this, Slayter had ordered a new change of course to take them back towards it. Before retiring to his stateroom below the bridge where he was billeted, Slayter told Lightoller to maintain the same course, keep a sharp look-out for land and let him know when it was sighted. When he had gone, Blair and Lightoller studied the chart once again. Neither officer was feeling too happy about the ship's position. Blair knew his job all right, and if there were any calculations that Lightoller would stake his life on they were Blair's, but right now the navigator was just about at the end of his tether. (Titanic Voyager: The Oddysey of C.H. Lightoller, Patrick Stenson)

On the 8th of September 1914, the day tragedy struck, there were confusing orders from the two captains:

Wikipedia: Captain Slayter had retired after his night watch, unaware of the situation, with orders to steer to Foula. Commander Smith took over the morning watch. Having previously disagreed with his naval superior about dodging around the island, he instructed the navigator to plot a course out to sea. Slayter must have felt the course change, as he reappeared on the bridge to countermand Smith's order and made what turned out to be a hasty and ill-informed judgement. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Oceanic_(1899)

Scottish Shipwrecks: Captain Slayter then retired to his cabin leaving Captain Smith in charge. Smith was not comfortable with the intended course and therefore ordered a change of course more to the west to take them out to sea away from Foula. It appears that Slayter felt the course change as he returned to the bridge and countermanded Smith’s order. Almost immediately the ship ran hard aground on the reef. (https://www.scottishshipwrecks.com/oceanic-2/)

Titanic Voyager: The chart was scrutinised by Smith, Lightoller and Blair. Foula had not yet been sighted and they did not expect it to be, as Blair's plot showed that on their present north-easterly heading they were still about 14 miles to the south and west of it. Smith continued to fret over the chart. He was most uneasy about steering for Foula. Taking the initiative, he made up his mind to change course without consulting Slayter. He would turn the ship due west towards open sea and away from any danger round the island or so he thought. At this stage no-one on the bridge believed the ship was in any real jeopardy though nagging doubt had prompted Blair to suggest taking soundings to be on the safe side. Smith rejected the idea. Even if the navigator was slightly out in his reckoning, visibility, despite a lingering mist, appeared to be a good four to five miles, which would give them plenty of time tỏ see any land ahead. Meanwhile the lookouts were told to keep a special watch aft on the starboard side where the island was expected to appear as the morning brightened and the horizon cleared. Land still had not been sighted when Lightoller's watch finished and he made way for Wiles.

It was twenty minutes after he retired to his cabin to rest that a cry from the crow's nest that land was dead ahead brought sudden consternation to the bridge. It was Foula. On the bridge all was confusion as they realised that instead of seeing the island slide by astern, they were heading straight for it. Blair had obviously been miles out in his reckoning. Smith had two choices open to him. He could either put the ship astern on the principle that if they had not hit anything going ahead the same would apply in reverse, or he could turn her away from the island and hope in that way to steer clear of trouble. He estimated that the island was still at least four miles off which, therefore, by his reckoning would put him well short of the Shaalds. He opted for the latter course and turned the ship several points to starboard with the apparent intention of bringing her round to the south again in a wide sweep. As Lightoller drifted off to sleep he was unaware of the panic on the bridge, where Slayter had just then chosen the opportune moment to arrive.

Now would see the culmination of the problems that had been simmering on the ship with two Captains. After quickly sizing up the situation Slayter, realising that they were closer to the island than Smith evidently thought, countermanded Smith's order and had the helm swung hard over in a sharp turn to starboard to get right away from it, while Blair was told to quickly take a fix on the land which was looming larger by the minute.

Moments later Blair came dashing out of the chartroom and yelled 'We're close to the Hoevdi Reef!' As he spoke, before there was even a chance to make a grab for the engine telegraphs. a sickening crunch reverberated through the Oceanic as she ground onto the wicked Shaalds and was driven further and more firmly onto them by the fast- running tide. (Titanic Voyager: The Oddysey of C.H. Lightoller, Patrick Stenson)

A rare image of the event - showing the HMS Oceanic in the grip of the Shaalds, with HMS Forward standing by as the liner's lifeboats, loaded up with 600 crew, are lowered. (Photograph: Titanic Voyager: The Odyssey of CH Lightoller by Patrick Stenson).

(Click image to enlarge)

Despite the damage, all persons aboard, more than 600 individuals, were carried to safety. Lightoller describes the evacuation:

The fact remains that early one morning she caught this outlying reef, and was pounded to pieces by the huge sea then running. Lying broadside on to the reef, with the tide setting strong on to it, she was held there, lifting and falling each time, with a horrible grinding crash. I know it nearly broke my heart to feel her going to bits under my very feet, after all these years. The sensation, as those knife-edged rocks ground and crunched their way through her bilge plates, was physically sickening.

How she held together long enough for us to get everyone out of her was a miracle in itself, and certainly testified to the good work put in by Harland and Wolff.

What with the heavy sea and swift current—to say nothing of the fog—we had our work cut out to get the stokers and engineers away without loss of life. With the seamen, and eventually the officers, although the weather conditions had become markedly worse, the operation was somewhat easier. Our much discussed Hebredian contingent certainly shone that day. The calm and collected manner in which they went about their work made it seem as if abandoning ship, under such trying conditions as then existed, was of daily occurrence with them—personally I was tremendously glad of their self-reliant help, and proud of their fearless ability. (Titanic and Other Ships, Charles Lightoller, 1935)

Almost exactly two weeks later, on 29th September, a massive gale hit the Shetlands and the HMS Oceanic disappeared. Due to the onset of First World War and a media blackout, what happened to the Oceanic was largely kept out of public view.

Another rare photograph of the Oceanic sinking. (Credit: www.wrecksite.eu)

(Click image to enlarge)

Court Martial - Blair Guilty?

A court martial was held and it seems that David Blair did not fair well at the proceedings:

At a court martial following the incident both Captains were exonerated of any wrong doing, but Oceanic’s officer, David Blair who was originally Titanic’s 2nd officer before the officer reshuffle, was reprimanded for not taking proper precautions to sound on the approaching island and for not immediately stopping the ship when he sighted land. (https://www.whitestarhistory.com/oceanic2)

For example the Birmingham Daily Post, 20 November 1914, ran with the headline: "DUE TO THE NEGLIGENCE OF NAVIGATING OFFICER" and stated that Lieutenant David Blair, R.N.R.... had been guilty of stranding the ship by omitting to take proper precautions to sound after experiencing abnormal compass deviation, and also by not suggesting an immediate stoppage of the engines on unexpectedly sighting land. The defence endeavoured to establish that the accused was not responsible, as the captain and commander had undertaken the direction of the ship and assumed responsibility." The Weekly Dispatch of London reported that he was also "ordered to be reprimanded. Commander Henry Smith, R.N.R., was acquitted on a similar charge." (The Weekly Dispatch, 22 November 1914)

Lightoller agreed with Blair's defence and does not blame his colleague:

The Oceanic was really far too big for that patrol and in consequence it was not long before she crashed on to one of the many outlying reefs and was lost. The fog was as thick as the proverbial hedge when she ripped up on the rocks; and in all fairness one could not lay the blame on the navigator—my old shipmate of many years, Davy Blair—trying as he was to work that great vessel amongst islands and mostly unknown currents. (Titanic and Other Ships, Lightoller, 1935)

Others agree with it being unfair:

At the subsequent court martial Lieutenant Blair took the bulk of the blame and was reprimanded for failing to take account of the tidal conditions when establishing the position of the ship. This judgement appears very unfair as retrospective calculation of the position established by Blair confirmed his readings at the time were correct and the stranding was therefore due to variations in the course steamed after the reading due to abnormal tide conditions in the area. Amazingly, both Captains Smith and Slayter were acquitted. (https://www.scottishshipwrecks.com/oceanic-2/)

Inger Sheil & Kerri Sundberg point out that the reprimand was "relatively mild":

In the court-martial hearings which followed, Lightoller’s role in the Oceanic disaster was deemed to be minimal because he was off duty at the time. The two captains were exonerated, even though they were both on the bridge when the accident occurred and despite the fact that Captain Smith rejected Blair’s suggestion that soundings be taken. In the end, Blair received the brunt of the blame, criticized for not taking soundings and not stopping the ship when Foula Island was spotted. Fortunately, Blair was not court-martialed for the incident. In fact, the resulting reprimand was relatively mild. ("Bridge Duty, Officers of the RMS Titanic," 1999, Inger Sheil & Kerri Sundberg)

Stenson believes Blair was "unlucky" although no further action was taken, but it left Blair a "disillusioned man":

"At the courts martial which followed back at the naval headquarters in Devonport, where Lightoller this time was grateful to be a witness merely on the fringe of the proceedings, it was Blair alone who came away with a blot on his record. Captain Smith and Captain Slayter were both completely exonerated. Once again Lightoller was observing the whitewash brush being liberally applied, but sadly this time at the expense of the unlucky Blair. The court found that he had been at fault for not taking the precaution of sounding, and not advising that the ship be instantly stopped when land was sighted. For some reason it was not taken into account that he did suggest taking soundings - a suggestion which Captain Smith rejected, and secondly, as both captains were on the bridge at the critical moment, surely it was their decision to stop the ship and not his? If Lightoller had once known what it felt like to be the whipping boy for everyone, now it was Blair's turn to sample a taste of it. However his reprimand was only minor and no further action would be taken against him. Nevertheless the navigator was left a disillusioned man. Recalling how Blair, by a blessing of fate, had escaped the demise of the Titanic Lightoller could not resist smiling a little to himself at the irony of his colleague's subsequent misfortune." (Titanic Voyager: The Oddysey of C.H. Lightoller, Patrick Stenson)

A painting of the Oceanic sinking. (Click image to enlarge)

See also...

Next... Navy & Career

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: