Side Menu:

Second Officer C.H.Lightoller

- British Inquiry: "Hand on the Whitewash Brush"

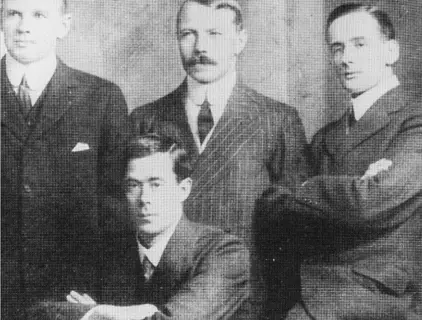

The four surviving Titanic officers, in a signed studio photograph, on their return to England. It is one of two only known photographs of the officers together. From left: Fifth officer Lowe, Third officer Pitman, Second officer Lightoller and Fourth officer Boxhall. (Click image to enlarge)

In England, an inquiry was instigated by the British Wreck Commissioner on behalf of the British Board of Trade, overseen by High Court judge Lord Mersey, and held in London from 2 May to 3 July 1912. The hearings took place mainly at the London Scottish Drill Hall, at 59 Buckingham Gate, London SW1. There were a total of 42 days of official investigation.

The second photograph of Titanic's surviving officers is more serious.

From left: Second officer Lightoller, Fifth officer Lowe, Third officer

Pitman, Fourth officer Boxhall. (Click to enlarge)

Lightoller was once again one of the key witnesses and appeared over the course of 3 days - the 12th ,13th and 14th days of the Inquiry. His opinion of this investigation was much higher than the US inquiry, but he also admits to also having his "hand on the whitewash brush" when he later wrote in his book:

“Such a contrast to the dignity and decorum of the court held by Lord Mersey in London, where the guiding spirit was a sailor in essence, and who insisted, when necessary, that any cross-questioner should at any rate be familiar with at least the rudiments of the sea…. [I]n London it was necessary to keep one’s hand on the whitewash brush. Sharp questions that needed careful answers if one was to avoid a pitfall, carefully and subtly dug, leading to a pinning down of blame on to someone’s luckless shoulders.”(47.)

Lightoller also described himself as a "whipping boy":

“I am never likely to forget that long drawn out battle of wits, where it seemed that I must hold that unenviable position of whipping boy to the whole lot of them. Pull devil, pull baker, till it looked as if they would pretty well succeed in pulling my hide off completely, each seemed to want his bit. I know when it was all over I felt more like a legal doormat than a Mail Boat Officer."(47.)

Lightoller (right) smoking a pipe withThird officer

Pitman, after they arrived in Liverpool, May 11th,

1912 aboard the Adriatic. (Click image to enlarge)

According to "The Other Side of the Night: The Carpathia, the Californian and the Night the Titanic was Lost" by Daniel Allen Butler Sylvia Lightoller "faithfully attended every session of the Board of Trade Inquiry. To her it as a question of keeping faith with her husband's colleagues, living and dead."

Interestingly, Lightoller pinned the blame on wireless operator Jack Phillips not passing on an ice message from the Mesaba. Not only was Phillips not there to defend himself of this accusation, as he had gone down with the Titanic, he was also not a White Star Line employee. So you could argue he was a convenient scapegoat for Lightoller to choose.

But the British Wreck Commissioner, Lord Mersey was indeed unhappy with Lightoller's testimony, saying it was "not at all satisfactory." In connection to his testimony regarding calculating ice ahead he said:

"Lightoller’s evidence upon that point is, in my opinion, not at all satisfactory. I have been examining it very carefully, and it seems to contain contradictions and statements which it is very difficult to reconcile with what we know to have been the facts."(24.)

Lightoller (right) at the British Board of

Trade Inquiry.

In regards to a conversation with Captain Smith about the conditions on the night, the Commissioner also doubted Lightoller's evidence and theory that a calm sea and moonless night made icebergs hard to detect:

The Commissioner: ‘I suppose I am obliged to accept Lightoller’s statement about that conversation?’

The Attorney-General: ‘Well, I do not know.’

The Commissioner: ‘I do not like these precise memories; I doubt their existence. However, there it is.’

The Attorney-General: ‘There it is, and we have to deal with it on the evidence. The reason why I am dealing with Lightoller’s evidence is because Lightoller is the only person who makes this excuse.’

The Commissioner: ‘Yes, and it sounds to me so like an excuse.’

The Attorney-General: ‘It is right to say this is it not— your Lordship is a better judge than I am from every point of view, and I was not here during the whole of the time when Lightoller was giving his evidence— that he did give it very well.’

The Commissioner: ‘It is to be remembered that he told exactly or practically the same story in America.’

The Attorney-General: ‘Yes, from the first. I think it is right to say with regard to Lightoller, is it not, that he gave his evidence very well.’

The Commissioner: ‘He gave it remarkably well.’

The Attorney-General: ‘Too well your Lordship thinks?’

The Commissioner: ‘Well, remarkably well.’(24.)

Lightoller attending the British Board of Trade

investigation, with his wife Sylvia, and possibly

Fourth officer Boxhall to his left.

(Click image to enlarge)

The British Inquiry ultimately decided that the disaster was "due to collision with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship was being navigated" but did in contrast not condemn the failures of the Board of Trade, the White Star Line or Titanic's captain, Edward Smith. Lightoller picks up on this in book:

“A washing of dirty linen would help no one. The B.O.T. had passed that ship as in all respects fit for sea in every sense of the word, with sufficient margin of safety for everyone on board. Now the B.O.T. was holding an enquiry in to the loss of that ship—hence the whitewash brush. Personally, I had no desire that blame should be attributed either to the B.O.T. or the White Star Line, though in all conscience it was a difficult task, when handled by some of the cleverest legal minds in England, striving tooth and nail to prove the inadequacy here, the lack there, when one had known, full well, and for many years, the ever-present possibility of just such a disaster. I think in the end the B.O.T. and the White Star Line won.”(47.)

The report's recommendations, along with those of the earlier United States Senate inquiry did lead to changes in safety practices following the disaster but which Lightoller believes is "ridiculous". For example in regards to the boat deck he writes:

No longer is the Boat-Deck almost wholly set aside as a recreation ground for passengers, with the smallest number of boats relegated to the least possible space. In fact, the pendulum has swing to the other extreme and the margin of safety reached the ridiculous.”(47.)

Ultimately, despite his efforts to protect his employer, Lightoller felt hard done by, with no appreciation for his efforts:

Perhaps the heads of the White Star Line didn’t quite realise just what an endless strain it had all been, falling on one man’s luckless shoulders, as it needs must, being the sole survivor out of so many departments—fortunately they were broad. Still, just that word of thanks which was lacking, which when the Titanic Enquiry was all over would have been very much appreciated. It must have been a curious psychology that governed the managers of that magnificent Line. Promotion and service in their Western Ocean Mail Boats was the mark of their highest approval. Both these tokens came my way, and fifteen of my twenty years under the red Burgee with its silver star, were spent in the Atlantic Mail. Yet, when after twenty years of service I came to bury my anchor, and awaited their pleasure at headquarters, for the last time, there was a brief, “Oh, you are leaving us, are you. Well, Good-bye.” A curious people!”(47.)

A close up of Lightoller from the officer's group photo.

Back to Work and Faith

On the 23rd of July of 1912, White Star Line made Lightoller First Officer of the Majestic, aboard which he served until the 5th of November that year.

During this time period, in October 1912, Lightoller published a short article in The Christian Science Journal for October, 1912, page 414, under the title of "Testimonies From the Field". Most notably, he credited his faith in a divine power for his survival, concluding that" with God all things are possible." Lightoller was apparently a Christian Scientist and this was the first of several articles and letters he wrote for the Christian Science publication. You can read these in full in the following article.

Lightoller photographed in August 1912 while serving

as First Officer on board White Star's R.M.S. Majestic.

(Click to enlarge)

Perhaps things were looking up for Lightoller when on the 5th of November he was promoted from First officer to Chief Officer, although no doubt frustratingly, three weeks later he was demoted to First officer again. He was shuffled back and forth between Chief Officer aboard the Suevic and Majestic and First Officer for the Oceanic in 1913 and 1914. Also, in May 1913 he received a promotion from Sub-Lieutenant to Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve.

In the family he also experienced both joy and tragedy; on the 11th April 1913 his daughter Sylvia Mavis was born, almost a year after the Titanic tragedy. But then in December 1913 his father, Frederick Lightoller commits suicide in Waipawa, New Zealand. He never mentions this in his articles or autobiography so we do not know his feelings on the matter.

But war clouds were brewing over Europe and soon Lightoller would be drawn into another pivotal moment in history: the first world war.