Side Menu:

Captain E.J. Smith - Personality, Reputation and Retirement

Studio portrait of E. J. Smith taken in New York in

1909 (8ins. x 6ins.) showing

Smith without his

uniform or cap. (Click to enlarge)

Due to the legendary status that Captain Smith has attained, it is frequently difficult to ascertain exactly who he was - his personality, character and reputation. It is only through those who knew him that we can gain some insight into the man behind the uniform.

According to The Examiner of Friday 26th April 1912, they had the following description:

"Captain Smith was an ideal sort of skipper," said one officer who had served under the commodore of the fleet for over a year whilst the latter was in charge of the Adriatic. "He was a fine looking chap," the officer continued, "standing well over six feet in height, and with the carriage and bearing of a man of only half his sixty odd years. Distinction and a somewhat patriarchal demeanour were conferred upon him by his carefully-trimmed white beard. Captain Smith by reason of his sociability was a great man amongst the passengers. He was very well read, had a great knowledge of the world, and was an excellent narrator of a fund of excellent stories."

Geoffrey Marcus described Smith in his book The Maiden Voyage as a "big man, generally regarded as the beau ideal of a Western Ocean Mail Boat Commander. His personality radiated authority, tact, good humor, and confidence. He had a pleasant, quiet voice and a ready smile. A natural leader and a fine seaman, Captain Smith was popular alike with officers and men."

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) has the following description: "A large, imposing figure, who kept a pet Irish wolfhound, and an inveterate cigar-smoker, Smith was a popular and trusted captain among the prestigious passengers who made regular Atlantic crossings on White Star liners."

As for this officers, they were generally very positive. Sixth officer James Moody wrote to his sister about Smith that "though I believe he's an awful stickler for discipline he's popular with everybody,"

Second officer Lightoller wrote about Smith in his book, Titanic and Other Ships:

Captain E.J. Smith, Commodore of the Line came over a little later on. Captain Smith, or “E.J.” as he was familiarly and affectionately known, was quite a character in the shipping world. Tall, full whiskered and broad. At first sight you would think to yourself “Here’s a typical Western Ocean Captain.” “Bluff, hearty, and I’ll bet he’s got a voice like a foghorn.” As a matter of fact, he had a pleasant quiet voice and invariable smile. A voice he rarely raised above a conversational tone—not to say he couldn’t; in fact, I have often heard him bark an order that made a man come to himself with a bump. He was a great favourite, and a man any officer would give his ears to sail under...

Captain E.J. was one of the ablest Skippers on the Atlantic, and accusations of recklessness, carelessness, not taking due precautions, or driving his ship at too high a speed, were absolutely, and utterly unfounded; but the armchair complaint is a very common disease, and generally accepted as one of the necessary evils from which the sea-farer is condemned to suffer. (47.)

Samuel Rule, a steward who served under Smith numerous times, spoke of Captain Smith after the Titanic disaster and said: “A better man never walked a deck. His crew knew him to be a good, kind-hearted man, and we looked upon him as a sort of father.” (61.)

Captain Edward John Smith seen with his

trademark cigar and his pet Borzoi or Russian

wolfhound - White Star R.M.S. Adriatic c.1907

(Click to enlarge)

J. E. Hodder Williams of Hodder and Stoughton Publishers would also remember him fondly. “We crossed with him on many ships and in many companies, through seas fair and foul, and to us he was and will ever be, the perfect sea captain …. He had an infinate [sic] respect – I think that is the right word – for the sea. Absolutely fearless, he had no illusions as to man’s power in the face of the infinate [sic].” (Titanic Officers and a Gentleman 61.))

Kate Douglas Wiggin, author of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, had ample opportunity to get to know Captain Smith. “The routine of life on the smaller, slower ships of earlier years made it possible to form real friendships …. This was my pleasure and privilege, season after season, for I crossed the ocean with Captain Smith twenty times or more …. Captain Smith was an admirable host: modest, dignified, appreciative; his own contributions to the conversation showing not only the quantity of his information, but the high quality of his mind …. His blunt, straightforward, seamanlike speech, his keen sense of humor, his essential kindness, his sunny smile – all these seemed to be just so many visible expressions of a character intrinsically upright and trustworthy.” 61.)

Mrs Ann O'Donnell, of 3726 Bryant Street, San Francisco, who knew Smith from the time he was a teenager, was quoted in an April 19th, 1912 newspaper:

"He was a kindly, thoughtful and genial man. He never rose above his position, and I never knew him to forget that once he was listed on the ship's books as merely an able seaman. He never forgot his friends and loved to cherish memories of the days spent in the little town in England. Captain Smith was one of the bravest men that ever lived. He was never know to have flinched in the face of the most serious danger. The utmost confidence was always placed in him by the owners of the ships he commanded. He was thoroughly reliable and conscientious, and was loved by everyone who knew him. They could not help it, for he seemed to be a man who was a friend to all who understood him." (Syndicated newspaper account, San Francisco, April 19th, 1912)

Blame and Reputation

In a letter of Thursday 6th June 1912 his widow Eleanor wrote that she is "proud to bear his name. I wish you could know- read all the magnificent tributes paid to him. I never knew any one man create such esteem and love as he had the power of doing, and no son of England died a more noble death; he and Captain Gates may stand together and a way up higher than the highest… Did you ever hear of dear Ted saving the child? It is quite true and so like him. " But she also expressed concern over the Inquiries, writing: " I have had to face the all too-horrible actions on the part of the Congress working up the "Titanic" claims. They intend to make out faulty navigation. By lies only can they succeed and has been proved by the experience of the "Olympic" case, lies do succeed in the hands of the evil one."

It is very easy to point the finger of blame when that person is no longer alive to defend themselves. The early signs of this came when Senator William Alden Smith who chaired the United States Inquiry, gave his report to Congress on May 28, 1912. He clearly stated that the Captain’s “indifference to danger was one of the direct and contributing causes of this unnecessary tragedy, while his own willingness to die was the expiating evidence of his fitness to live.” At least Senator Smith also included some kind words, saying, “Captain Smith knew the sea and his clear eye and steady hand had often guided his ship through dangerous paths. For forty years, storms sought in vain to vex him or menace his craft. Each new advancing type of ship built by his company was handed over to him as a reward for faithful services and as evidence of confidence in his skill. Strong of limb, intent of purpose, pure in character, dauntless as a sailor could be, he walked the deck of this majestic structure as master of her keel.”(25.)

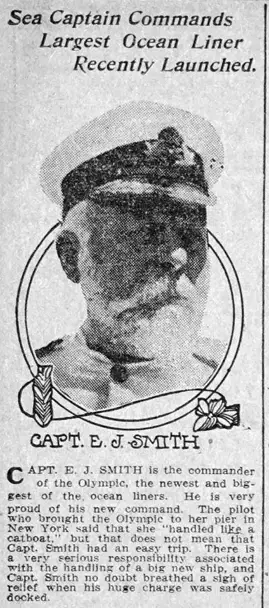

A newspaper article about the Olympic

emphasising Smith's "serious responsibility."

(Click image to enlarge)

At the subsequent British Inquiry, Lord Mersey’s summary made it clear that it was easy to realize, in retrospect, that Captain Smith should have changed course or at least slowed down. However, his actions conformed to the practices of the day. “In these circumstances I am not able to blame Captain Smith. He had not the experience which his own misfortunate has afforded to those whom he has left behind, and he was doing only that which other skilled men would have done in the same position.”… “He [Captain Smith] made a mistake, a very grievous mistake, but one in which, in the face of practice and of past experience, negligence cannot be said to have had any part; and in the absence of negligence it is, in my opinion, impossible to fix Captain Smith with blame. It is, however, to be hoped that the last has been heard of the practice and that for the future it will be abandoned for what we now know to be more prudent and wiser measures. What was a mistake in the case of the ‘Titanic’ would without doubt be negligence in any similar case in the future.” In a summary found in the Daily Sketch of Thursday 20th June 1912, it quoted Lord Mersey as saying that it was "not the practice to find negligence ahainst a dead man" which was confirmed by Mr Aspinall, an Admiralty counsel for the Government who said: "I know of no rule, but the Courts have always shown great reluctance to find negligence against a dead man."

However there were those who saw heroism in his actions.

Speed - Negligence or Complacency?

The most frequent criticism of Smith was that Titanic was traveling too fast into an area of icebergs. Often the word "reckless" is used. It must be understood that this was the norm for the time - but only when the weather was clear and there was good visibility, weather conditions that existed on Sunday the 14th of April. Captain Smith was not the only master to do this - it was common practice. Maintaining high speed was for several critical reasons:

* In 1912 ships such as the Titanic were not cruise ships - they were passenger liners for mass transportation of people and cargo, much like jet aircrafts today, and had strict schedules to keep. Titanic was additionally a Royal Mail Ship (RMS) so had deadlines to meet. Hence, time was of the essence.

* Speed aided manoeuvrability. Long ships such as the Titanic turned faster at speed and so it was considered prudent to maintain speed so as to avoid ice or other obstacles.

* Maintaining speed also meant exiting the danger zoon quicker and thus exposed to risk over a shorter duration.

* On the night of April 14th, 1912, visibility was excellent there was no reason to slow down.

Captain Smith was not inheritently a reckless captain. The two previous incidents (the Olympic-Hawke collision and Titanic-New York near collision) took place when his ship was under compulsory pilotage (Trinity House Pilot George Bowyer was in command on both occasions). And indeed, according to author Mark Chirnisde we have an example of how Captain Smith behaved as the commander of the largest ship in the world on her maiden voyage, from June 1911. On the Sunday, the Olympic encountered fog and was slowed down for a few hours, delaying her 1 1/2 hours in total. If similar had happend to Titanic almost undoubtedly Smith would have slowed the Titanic down.

When Lightoller was told at the British inquiry that it "was recklessness, utter recklessness, in view of the conditions to proceed at 21 ½ knots" Lightoller replied that "then all I can say is that recklessness applies to practically every commander and every ship crossing the Atlantic Ocean."

Indeed we have evidence from other contemporary captains testifying that Smith was adhering to the norms of his day:

1. Captain John Pritchard, who formerly commanded Cunard's record setting Mauretania, which was capable of 26 knots, said "should only slacken speed if the weather conditions were unfavourable." (The Cambria Daily Leader, 24 June 1913). At the British Titanic inquiry, on day 27, he testified under oath that even with "information that there was a probability of your meeting ice on your course" he would maintain speed: "As long as the weather is clear I always go full speed." Pritchard also explained that this was in his experience a "universal practice" - based on his time commanding Cunard ships between Liverpool and New York for 18 years. He also noted that if following the southern track - as did Captain Smith - he had "never got into an ice-field. We do not go North, you know; we go on the southern tracks this time of year." As for lookouts, he would not double them when in "clear weather." Captain Pritchard on the bridge of the Mauretania, November 1907. A photograph of Smith that accompanied the

2. Captain Hugh Young, of the Anchor Line, with 37 years experience crossing the Atlantic on the New York trade, testified under oath that if ice were reported, he "should keep my course and maintain my speed" in clear weather. He also confirmed this was a "universal practice" (British Inquiry, Day 27)

Pritchard and ten other captains testified under oath that they would have

maintained speed and not put on extra lookouts in clear

conditions - exactly as Captain Smith.

(Click image to enlarge)

3. Captain William Stewart, Canadian Pacific, worked for 35 years on the trade between Liverpool and Canada. He was posed with the question if you "were given information that you might meet ice and that your course would take you through the place where you might meet ice, and meet it at night, would you reduce your speed?" His answer was: "No, not as long as it was clear." He was asked further, "if you had information that you might meet field ice, would you still maintain your speed?" and responded similarly: "Until I saw it, and then I should do what I thought proper." "(British Inquiry, Day 27)

4. The evidence of Pritchard, Young and Stewart was also confirmed by Captain John A. Fairfull, of the Allan Line, working the Atlantic for 21 years. He was asked "Is your practice in accordance with theirs?" And he answered "All except that when we get to the ice track in an Allan steamer, besides having a look-out in the crow's-nest, we put a man on the stem head at night." (British Inquiry, Day 27)

"R.M.S. TITANIC: Hardbound Journal of

Commerce report into the Titanic Inquiry (British),

printed by the Journal of Commerce in 1912

(Credit Connor Nelson)

6. Captain Frederick Passow, who had been a captain on the North Atlantic for 28 years, in the American Line, and who had crossed about 700 times, testified that he "had a very large experience of ice" and yet did not slacken his speed for ice as long as the weather was quite clear: "Not as long as it was quite clear - no, not until we saw it...when it is absolutely clear we do not slow down for ice." (British Inquiry, Day 21)

7. Captain Bertram F. Hayes, of the White Star Line, testified that when a position of reported ice he would continue "at the same rate of speed...No alteration...it is the practice all over the world so far as I know - every ship that crosses the Atlantic... Ice does not make any difference to speed in clear weather. You can always see ice then." (British Inquiry, Day 21)

8. Benjamin Steele, marine superintendent at Southampton for the White Star Line, and master mariner with an Extra Master's certificate of 19 years having been at sea "about 26 or 27 years" confirmed the practice of "not slackening speed on account of ice as long as the weather is clear" by responding "It is. I have never known any other practice."(British Inquiry, Day 21)

9. Captain Richard Jones, master of the SS Canada of the Dominion Line, and in the Canadian service for 27 years testified that his ship was stopped by ice on the 11th of April 1912. However he also confirmed that after receiving messages about the ice he continueed at full speed ahead, considering it a usual practice. He said: "I should think it would be just as safe to go full speed with 22 knots... we always make what speed we can..we always try to get through the ice track as quickly as possible in clear weather."(British Inquiry, Day 24)

10. Captain Edwin Cannons, master with the Atlantic Transport Company with 25 years’ experience in the North Atlantic noted that he had "never seen field ice on the southern track." If an iceberg is sighted he testifed that "I keep my speed...Both day and night...I have never had any difficulty to clear when I have met ice ahead." If ice is reported he said: "I should maintain my speed and keep an exceptionally sharp look-out... to maintain speed until the ice is seen." However, if was clear he would not double the look-out. (British Inquiry, Day 24)

11. Captain John Ranson of White Star Line’s Baltic, on the Liverpool-New York run also confirmed the standard practice: "We go full speed whether there is ice reported or not...We keep up our speed... It has always been my practice." He also stated that it is the practice of all liners on that course, "for the last 21 years to my knowledge." and that he would not double the look-outs at night - "not in clear weather."(British Inquiry, Day 26)

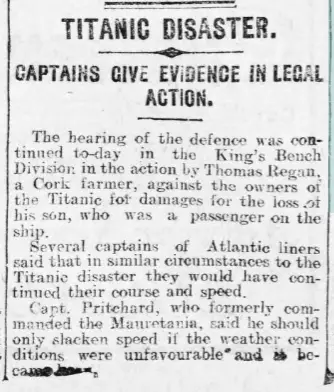

A year later North Atlantic captains of considerable

experience were still defending Smith's actions.

(The Cambria Daily Leader, 24 June 1913)

However, the only dissenting voice was that of Ernest Shackleton, the polar explorer, who said that he would have slowed down for ice; even in a vessel doing only six knots he would slow down. However, he was not a captain of a passenger and mail liner and undoubtedly was in closer proximity to ice due to the nature of his exploration, so can not be an accurate guide as to what a captain of a ship on the North Atlantic passenger and mail service would be expected to do.

Otherwise, without exception, 11 captains, all experienced in the North Atlantic, some from competitor lines, confirmed that what Captain Smith did on the night of April 14th was "standard practice."

The British Inquiry was not the only occasion that North Atlantic captains came to the late Captain Smith's defence. More than a year later, according to the June 24th, 1913 edition of The Cambria Daily Leader they appeared in court again, this time in a case brought by Thomas Regan, a Cork farmer, against the White Star Line, for the loss of his son. "Several captains of Atlantic liners said that in similar circumstances to the Titanic disaster they would have continued their course and speed. Capt. Pritchard, who formerly commanded the Mauritania, said he should only slacken speed it the weather conditions were unfavourable" (The Cambria Daily Leader, 24 June 1913)

However the notion that Smith was traveling at a "reckless" speed will likely never go away. As foretold by Lightoller in his book, "Titanic and Other Ships": "Captain E.J. was one of the ablest Skippers on the Atlantic, and accusations of recklessness, carelessness, not taking due precautions, or driving his ship at too high a speed, were absolutely, and utterly unfounded; but the armchair complaint is a very common disease, and generally accepted as one of the necessary evils from which the sea-farer is condemned to suffer."

Heroism

Captain V. W. Hickson, who had served under Smith many years before, described him as “the nerviest and brainiest man in the service. If Captain Smith was in command of the Titanic, then there was a hero in charge when deeds of heroism were called for.”

Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club said "He was doing everything in his power to get women in these boats, and to see that they were lowered properly. I thought he was doing his duty in regard to the lowering of the boats".

One of Smith’s friends, identified by the press as Dr. Williams, had asked the Captain what he would do if the Adriatic struck an iceberg and was seriously damaged. Smith’s reply was that “some of us would go to the bottom with the ship.” Thus Williams believed Smith went down with the Titanic when the end came, as did one of Smith’s boyhood friends, William Jones. “Ted Smith passed away just as he would have loved to do. To stand on the bridge of his vessel and go down with her was characteristic of all his actions when we were boys together.”

But in the book "Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Cenntenial Repraisal" it directly blames Smith for the low lifeboat numbers:

"It seems better results could have been obtained if there was better organisation and communication. For example Captain Smith made no special effort to inform many of his officers that Carpathia was on the way, or how long Titanic actually had left. Key officers, including Lightoller and Pitman, were never told, and the urgency of the situation was not recognised until much later on." (62.)

In a Daze?

Captain Smith in his summer white uniform

aboard R.M.S Olympic, 1911

(Click image to enlarge)

Possibly due to Second officer Lightoller mentioning in his book that he had to approach and ask Smith for permission to begin loading women and children into the lifeboats, there has been a suggestion that the captain was in a 'daze' and ineffective in the face of disaster - which has often been carried over the film portrayals. But as seen in this website - with the list of his subsequent actions on the night, he was definitely in charge and full of action during the crisis.

J Kent Layton, Bill Wormstedt and Tad Fitch are the authors of On A Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of the RMS Titanic, wrote the following for History Extra (April 13, 2018):

"Smith, who was aged 62 at the time, was seen moving from one place to another, giving careful and thoughtful orders. Off-duty when the iceberg was struck, Smith quickly took charge, personally making two inspection trips below deck to look for damage, and preparing the wireless men for the possibility of having to call for help. He even erred on the side of caution by preparing the lifeboats for loading before he was certain that the ship was sinking. Smith was observed all around the decks, personally overseeing and helping to load the lifeboats, interacting with passengers, and striking a delicate balance between trying to instill urgency to follow evacuation orders while simultaneously attempting to dissuade panic." (History Extra, April 13, 2018)

Impending Retirement?

One of the most repeated rumours is that Captain Smith was going to retire after the maiden voyage, which adds a bitter irony to the tragedy. There has been substantial controversy over this issue. Is it true or unlikely legend? Here are some key factors to consider:

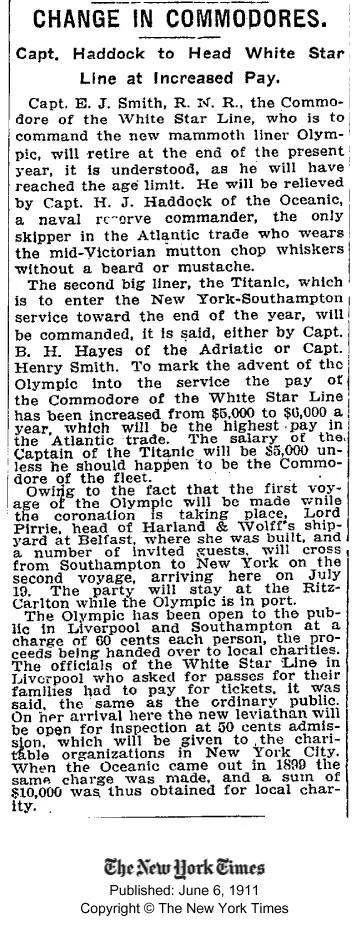

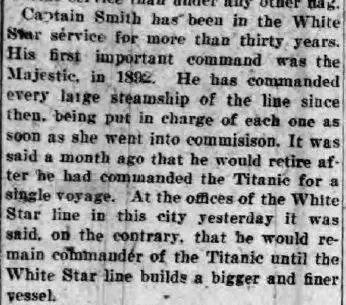

Age limit: Although Smith signed on to Titanic aged "59" he was actually 62. The third ship in the Olympic class series would take at least another two years (Britannic did not enter service until 1915 - 3 years later) by which time he would be 64 years old. In 1910 Cunard put an age limit of 60 years for captains of their new ships Mauretania and Lusitania. 54.). However, this was not a legal requirement. The New York Times of June 6, 1911, An April 10th, 1912 newspaper report denying reports

announces Smith's retirement at the end of 1911.

1911 Newspaper reports of retirement: The New York Times of June 6, 1911 reported: "Capt. E.J. Smith, R.N.R. the Commodore of the White Star Line, who is to command the new mammoth liner Olympic, will retire at the end of the present year, it is understood, as he will have reached his age limit. He will be relieved by Capt. H.J. Haddock of the Oceanic." There was never any correction or retraction of this before or after the Titanic disaster. However The New York Times did publish another article dated November 19, 1911 which stated that Captain Smith would retire "next Summer on reaching the age limit" and be replaced with Captain Haddock - indicating he would continue in command of Titanic for the months of April through to June 1912.

Captain Smith would retire after Titanic's maiden voyage.

Publicity: Since Captain Smith's name guaranteed bookings, author Gary Cooper has suggested that the White Star Line might even have encouraged the rumours of retirement, not denying them until the last moment, in order to benefit from bookings by passengers not wanting to miss out on the famous EJ's 'last' voyage. 60.)

Historian's recent conclusion: According to the authors of the book "On A Sea of Glass" - Titanic historians Bill Wormstedt, J. Kent Layton, and Tad Fitch, retirement was likely: "So although far more ironic in hindsight, it seems Captain Smith's career was extended for a few months past the end of 1911 in order to give him the honor of taking out the Titanic. Not only would this have been a wonderful 'thank you' from a grateful company, but it would have served a dual purpose of ensuring that a skipper experienced with ships of Titanic's ilk would be at her helm during the maiden voyage."

While it was likely Smith would indeed retire after Titanic's maiden voyage the reality is that we do not know how soon after the voyage it would happen. So it is inaccurate to state that it was his "last voyage" - perhaps it may have been, or perhaps he would have stayed on for several more, retiring once Titanic had settled in with Haddock in command. We simply will never know. The fact that Smith wrote down his age as 59 on Titanic's documents indicates perhaps some acknowledgement that he was now over the age limit. And he may well have wanted to retire anyway. But I do not know of any record of his widow Eleanor making a point of it being his "last voyage" which to me indicates while he was on the verge of retirement, it was not set in stone.

If this website has been of some help, please consider supporting it with a coffee

to ensure it can continue. It can be anonymous. Anything helps!: